Existing member? Log in and continue learning

See if you like it, start the course for free!

Unlock full course by purchasing a membership

What is an Observable?

What is an Observable?

What’s the big deal with observable streams? Why should we care and why

should we use them? We certainly don’t need to. Using observables is something

that is very common in Angular because Angular itself relies a lot on

observables internally, and it provides us a lot features in the form of

observable streams. We have seen some of these already — the observable stream

from ActivatedRoute to get the parameters from the route for example.

In an Angular environment, using observables and RxJS (which is a library that makes it easier for us to work with observables) is quite natural since Angular uses this approach already. But, outside of Angular, there are plenty of applications that don’t use RxJS or observables at all. So, again, the question: what’s so special about observables and “reactive programming”?

It’s not an easy thing to explain, it’s easier once you have some experience with using observables in a reactive way, and also what the sorts of problems are that you face without observables. But… I will do my best to give a basic explanation anyway!

If you are new to observables I don’t expect you to absorb 100% of what is in this lesson. Even just taking a vague notion of how an observable works away from this lesson will be a big win, and you can always revisit this lesson later to help clarify concepts.

High Level Analogies

Before we get into the specifics, I think it is worthwhile considering some analogies/metaphors for reactive style programming. Some analogies work quite well for me, other analogies work well for others, and for some people these analogies may be completely useless.

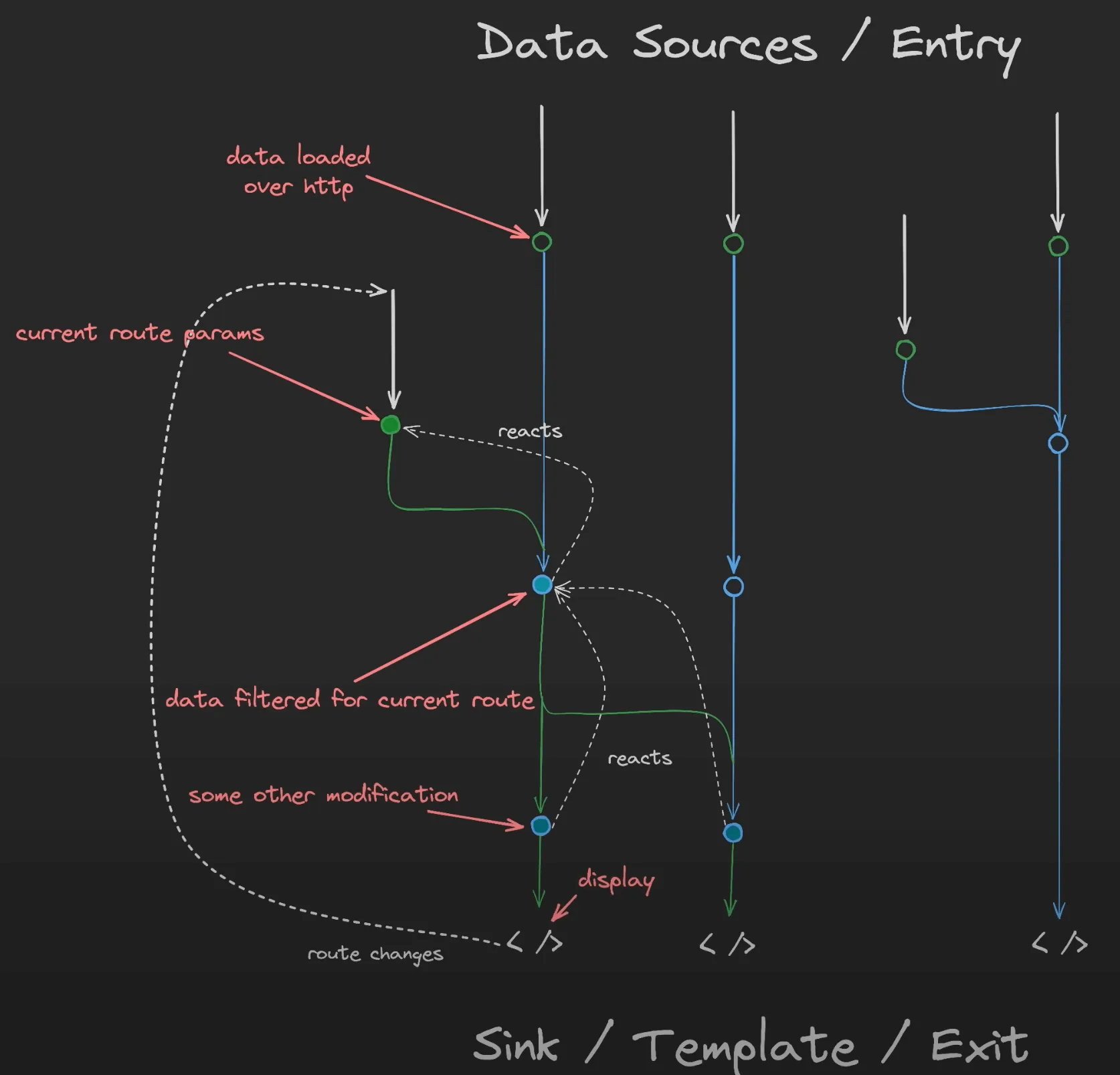

One of the key concepts is that we have data coming from some source (e.g.

an HTTP request) and it will end up in some sink (i.e. the destination for

that data, like a component’s template where the observable is subscribed to).

In the entire journey from the source to the sink, the data should never

leave the stream — meaning the stream should not be subscribed in order to

pull the data out — until it finally “comes out” at the destination.

Remember our A —> B diagram from the previous lesson? The diagram above is

a more realistic example of that. Each circle could be an A or a B or a C

— some reactive thing in the application that is reacting to other things

changing. We start at the source at the top, and things combine together and

react to each other until they are finally displayed in the template. It is

only that very last step, at the template, where we subscribe to pull the

values out of the stream.

As soon as we subscribe we are leaving the reactive paradigm — because once

you subscribe things can no longer automatically react to other things

changing (you would then have to do this manually, or, “imperatively” — more on

that later). We generally want one unbroken stream all the way to the

destination.

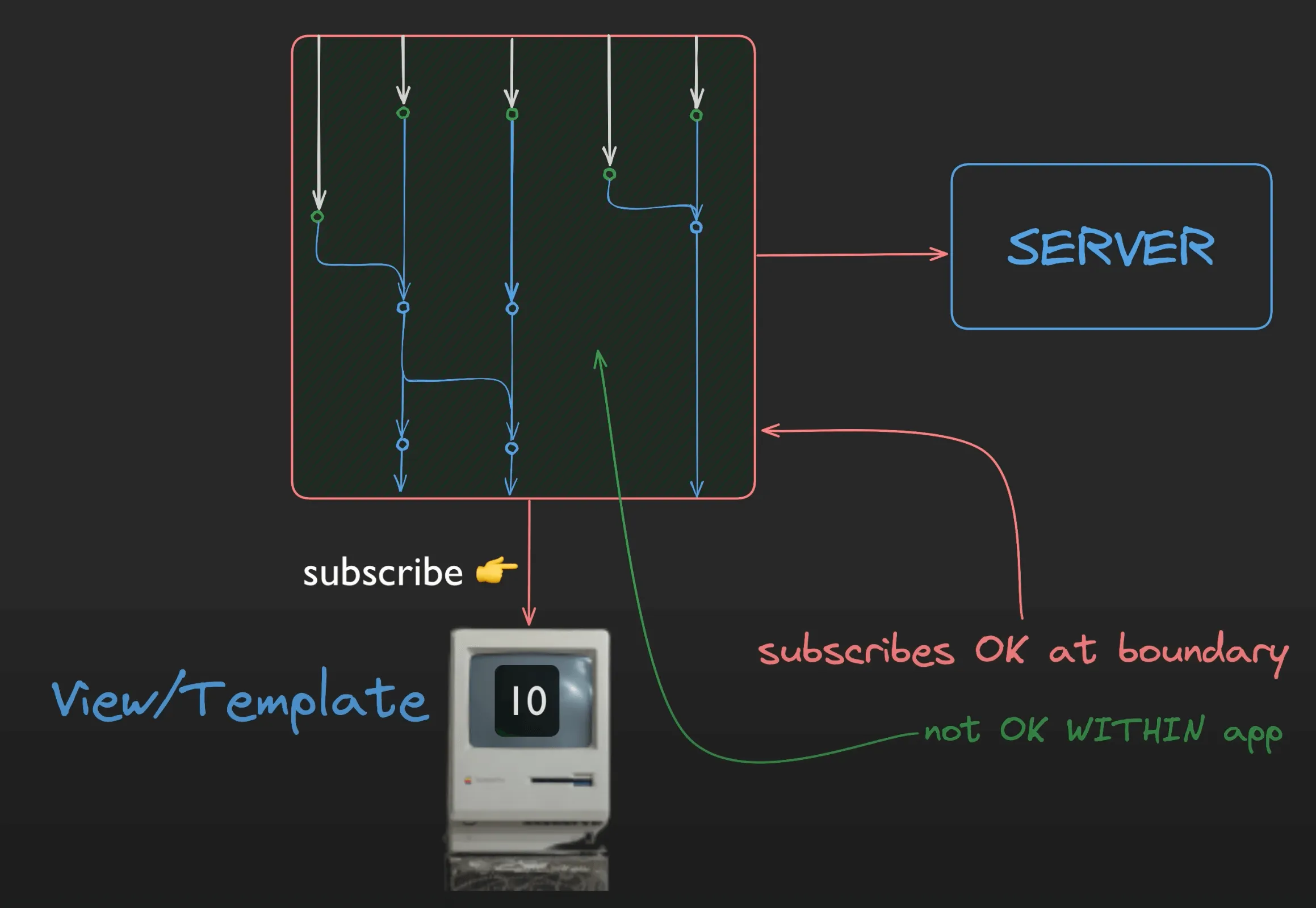

The diagram above is an expanded way to visualise this. All of the data flowing

through our application should remain in streams and not be subscribed to

whilst it is within our application (i.e. inside the box). But when we are

taking data “out” of the application — to display it to the user or perhaps send

it to a server — we can subscribe. We don’t need reactivity anymore because

the data is done.

Like a rain drop falling on a mountain, trickling into streams, merging with more streams into rivers which finally dump into the ocean. At that point, the droplets journey is done (at least if we don’t take this analogy too far).

This supplementary video may help explain this topic and also touches on some more concepts we will utilise later:

Another analogy that works particularly well for me is that of a factory with some kind of conveyor belt/assembly line (if you have ever played the game Factorio, kind of like that). We can imagine our source as being however our items get put onto the beginning of the conveyor belt. That item will continue along the conveyor belt until it finally gets dumped off at the end (i.e. the sink).

The important part of this metaphor is that, along the way, our item could be transformed based on whatever this factory is configured to do. Perhaps there are some machines that squash any items that pass through, or paint them, or cut them, or it does all of those things. Perhaps our conveyor belt even merges with other conveyor belts and items from other “streams” are combined with our item in some way. Maybe there is one of those cool robot arms that takes items from one conveyor belt and moves them to another one. At the end of this process, at our sink, we get the result of whatever happens when our items pass through this pre-configured factory.

This is precisely what happens with values in observable streams with reactive programming. Our observable stream is like the conveyor belt, the operators we will use to modify the data passing through the streams are like the factory gadgets modifying and merging things on the conveyor belt, and the values in our streams are like the items on the conveyor belt.

I won’t go into other analogies in as much detail, but they are all more or less the same — situations where something “flows” from one place to another. It might also help you to think of:

- Instead of a conveyor belt/factory analogy, we could also use a plumbing analogy of pipes with different shapes and connectors with water passing through them

- Electricity and circuits is another good one — we have some source of power, all of the “values” (the electricity) stay in the wires and we can “modify” this stream of electricity along the way in a sense (e.g. converting voltages), and then the values “come out” in the sink which in this case might be something like a lightbulb

These analogies might not mean much to you now, but as we learn more about observables and reactive programming, revisit these in your head and see if they do anything for you.

The Observer Pattern

In the Angular space, the RxJS library is synonymous with observables. I think it is common for people to think that the concept of an observable is an “RxJS thing”.

However, like some other things we have seen, the concept of an observable is part of a general software design pattern — specifically, the observer pattern. It’s worth taking a quick look at this pattern to help remove some of the mystery around observables. Observables seem like these highly complex magic things — “streaming” data… how cool is that? Must be some real fancy programming going on there.

At its core, the role of the observer pattern is to connect a producer of values to one or more observers of those values. We could represent an observable as a simple function that accepts an observer:

const myObservable$ = (observer) => {

}The role of the myObservable$ function here is to produce some values, and

then notify the observer that was passed to it. An observer is just an

object that implements three notifier methods called next, complete, and

error:

const observer = { next: (data) => console.log('My next was called with', data), complete: () => console.log('The observable has finished emitting data'), error: (err) => console.log('The following error ocurred', err)}The observer defines how we want to handle the values that are produced by

the observable. In a sense, this object is a way for the observer to give

the observable a way to contact it.

Let’s say that our myObservable$ observable just emits the values from 1

through to 5. That observable would look like this:

const myObservable$ = (observer) => { observer.next(1); observer.next(2); observer.next(3); observer.next(4); observer.next(5); observer.complete();}Our myObservable$ function produces values in any way it wants, and calls the

next method on the observer that was passed in to notify it of the values

that were produced. Now to use this observable we need to subscribe to it and

pass it an observer. Our overly simplified notion of an observable does not

have the concept of calling a subscribe method as we would typically do, e.g:

const observer = { next: (data) => console.log('My next was called with', data), complete: () => console.log('The observable has finished emitting data'), error: (err) => console.log('The following error ocurred', err)}

myObservable$.subscribe(observer);Instead, we would use our simple version like this:

const observer = { next: (data) => console.log('My next was called with', data), complete: () => console.log('The observable has finished emitting data'), error: (err) => console.log('The following error ocurred', err)}

myObservable$(observer);But it’s the same basic idea. The code above would produce this in the console:

My next was called with 1My next was called with 2My next was called with 3My next was called with 4My next was called with 5The observable has finished emitting dataAt the beginning, we said that the role of an observable is to connect

a producer of values to one or more observers of those values. We can

reuse our myObservable$ we have created above with multiple different

observers if we want (or we could call it multiple times with the same

observer):

const observerOne = { next: (data) => console.log('My next was called with', data), complete: () => console.log('The observable has finished emitting data'), error: (err) => console.log('The following error ocurred', err)}

const observerTwo = { next: (data) => console.log('Double the data double the fun!', data * 2), complete: () => console.log('The observable has finished emitting data'), error: (err) => console.log('The following error ocurred', err)}

const observerThree = { next: (data) => console.log('You call that doubling?', data, data), complete: () => console.log('The observable has finished emitting data'), error: (err) => console.log('The following error ocurred', err)}

myObservable$(observerOne);myObservable$(observerTwo);myObservable$(observerThree);myObservable$(observerOne);Given these observers, and the observable we already defined, see if you can figure out what the output of the above will be.

Click here to reveal solution

Solution

This will result in the following output:

My next was called with 1My next was called with 2My next was called with 3My next was called with 4My next was called with 5The observable has finished emitting dataDouble the data double the fun! 2Double the data double the fun! 4Double the data double the fun! 6Double the data double the fun! 8Double the data double the fun! 10The observable has finished emitting dataYou call that doubling? 1 1You call that doubling? 2 2You call that doubling? 3 3You call that doubling? 4 4You call that doubling? 5 5The observable has finished emitting dataMy next was called with 1My next was called with 2My next was called with 3My next was called with 4My next was called with 5The observable has finished emitting dataThis supplementary videos walks through creating a very basic implementation of an observable:

Creating a Simple Observable

We have just looked at an overly simplified version of an observable that just

uses a simple function. Now, let’s create a slightly more realistic

implementation using a class that has an actual subscribe method just like

a real observable. This is closer to what a “real” observable looks like but

it’s still very simplified as we won’t be implementing the complete and

error functionality in the observable, nor will we have the ability to

unsubscribe.

interface Observer { next: (value: any) => void; error: (err: any) => void; complete: () => void;}

class Observable { constructor(private _subscribe: (observer: Observer) => void) {}

subscribe(observer: Observer) { this._subscribe(observer); }}Let’s see how we would use this Observable. Let’s create a new Observable

that emits the numbers 1 to 5:

const emitOneToFive$ = new Observable((observer) => { observer.next(1); observer.next(2); observer.next(3); observer.next(4); observer.next(5);});Remember that our Observable class accepts a function as a parameter:

constructor(private _subscribe: (observer: Observer) => void) {}This is the function we are passing in as the _subscribe:

(observer) => { observer.next(1); observer.next(2); observer.next(3); observer.next(4); observer.next(5);}This function takes whatever observer is passed to it and passes it values

using next. Our constructor sets up this passed in function as a member

variable called this._subscribe:

constructor(private _subscribe: (observer: Observer) => void) {}But it doesn’t actually call the function that we passed in. Like a real observable, it won’t actually do anything until it is subscribed to. That is what this method in the observable is for:

subscribe(observer: Observer) { this._subscribe(observer); }This method calls the _subscribe function that was set up by the constructor

when we created the observable, and it passes it whatever observer we subscribed

with. So, this is the observable we created:

const emitOneToFive$ = new Observable((observer) => { observer.next(1); observer.next(2); observer.next(3); observer.next(4); observer.next(5);});Which will do nothing initially, but if we subscribe to it by passing it an observer:

emitOneToFive$.subscribe({ next: (value) => console.log(value), error: (err) => {}, complete: () => {}})We should get the following logged out to the console:

12345It is worth noting that with a real observable from RxJS, it is not required to

pass in all three notifier methods for the observer. If you want to just handle

the next values you can do this:

emitOneToFive$.subscribe((value) => console.log(value));A real Observable also has the ability to unsubscribe. Imagine in our

scenario above that we wanted a stream that emitted one number per second,

starting at 1 and going up to infinity. We might want to stop receiving those

values at some point, and that is what unsubscribe is for. That is why we

implement Observable as a class, as we can nicely build these extra features

and guarantees into it. What we have so far is just the most basic example.

I don’t think it is worthwhile at this point to go and recreate all of RxJS from scratch, the idea is that this simple example should give you some intuition for what an observable actually is.

What is a Subject?

There is an important distinction between two different types of observables. We

have cold or unicast observables, and hot or multicast

observables. The implementation we just looked at above, and the actual

Observable implementation in RxJS, is a cold or unicast observable.

A Subject is a special type of Observable. It is special because:

- It is a hot or multicast observable

- It can be treated like any other normal observable (e.g. you can

subscribeto it) - It can also be treated like an

Observer(e.g. you can call thenext,error, andcompletemethods on it)

The tricky part here is getting an understanding of what differentiates

a hot or cold observable and why that matters. The main difference

between a Subject and a normal Observable, and why the former is hot and

the latter is cold, can be described in the way they connect producers

of the values to the consumers/observers of those values.

A cold observable connects one producer of values to one consumer/observer of values. A hot observable connects one producer of values to one or more consumers/observers of values.

With our observable example, the values are produced from within the observable itself:

const emitOneToFive$ = new Observable((observer) => { observer.next(1); observer.next(2); observer.next(3); observer.next(4); observer.next(5);});When we create the observable, we supply it with a function that will handle producing the values and notifying the observer of those values. The production of those values lives inside of the observable. This means that every time we subscribe to this observable we are re-running this value producing logic. A new “producer” of values is created for each subscription, so we only ever have this one-to-one relationship between the values being produced and the observers that are subscribing.

With a Subject, the values are produced from outside of the observable.

This means that we can have multiple observers subscribing to the one subject,

but we only have one set of values being produced and shared with all of the

observers. We are going to look at how to create our own simple version of

a Subject from scratch just like we did with the Observable, but first let’s

take a look at a usage example to demonstrate this inside/outside concept I am

talking about.

As we have just seen, this is how we would create an Observable using our

simple implementation:

const emitOneToFive$ = new Observable((observer) => { observer.next(1); observer.next(2); observer.next(3); observer.next(4); observer.next(5);});But this is how we would create a Subject:

const emitOneToFive$ = new Subject();The obvious difference here is that the Subject contains no logic for

producing the values. If we subscribe to the Observable and pass it an

observer that logs out the values:

emitOneToFive$.subscribe({ next: (value) => console.log(value), error: (err) => {}, complete: () => {}})We would immediately see:

12345If we subscribe with the same observer to a Subject we would see this:

Nothing happens… yet. Our subscriber is still listening, it just hasn’t

received any values yet because they haven’t been produced yet. They need to be

produced outside of the Subject. Since a Subject is also an Observer,

I could now call:

emitOneToFive$.next(1)Since we already have a subscriber for this Subject, as soon as we do this we

would see:

1Output to the console. Our stream has emitted one value now, and our one

subscriber has received that value. What happens if we subscribe to the

Subject again with a new observer?

emitOneToFive$.subscribe({ next: (value) => console.log(value), error: (err) => {}, complete: () => {}})What do you think this second subscriber to the Subject would get after

subscribing?

Click here to reveal solution

Solution

Nothing. The 1 has already been emitted and the second subscriber has missed

it. With a hot observable, the stream just exists in its own right and will

go on emitting values even if nobody is listening. If you’re late to the party,

too bad (there are actually different types of subjects we can create to deal

with situations like this).

If we now call next again on our Subject:

emitOneToFive$.next(2)Both subscribers will receive this new value:

22This demonstrates another key reason you might want to use a Subject — if you

need to trigger values emitting on a stream from outside of that observable, you

can use a Subject so that you have access to the next method. In a sense,

the next method provided by a Subject is like a proxy way to call the next

method of all of the observers currently subscribed to that Subject.

If we wanted, we could have used a Subject to hold our state in the todo app

instead of using signals:

todos$ = new BehaviorSubject<Todo[]>([]);

addTodo(todo: Todo) { const newTodos = [...this.todos$.value, todo]; this.todos$.next(newTodos);}We create a todos$ subject, which is actually a BehaviorSubject. This is

similar in spirit to a normal Subject but with some extra features.

A BehaviorSubject is supplied with an initial value — you can see we are

supplying it with an empty array as an initial value. Remember how with the

Subject if you subscribed too late you wouldn’t get any values? With

a BehaviorSubject it will always give new subscribers the last emitted value

(or the initial value if no values have been emitted yet). As well as that, it

also has a special value property that we can use to access the last emitted

value without subscribing.

The point is, we want to create a stream that we can subscribe to from anywhere

in the application, and we want to control producing values on that stream

from outside of the stream itself. So, we use a Subject. In this case,

when the addTodo method is called, which exists outside of the stream, we

want to emit new values on the stream (specifically, we want to emit our new

todos on that stream so anybody listening can get the new data).

There is one last important consideration about a cold observable and

a hot observable, or a unicast observable and a multicast

observable, or an Observable and a Subject. With an Observable the

production logic is executed for every new subscriber. With a Subject the

production logic is executed once and the results are shared with all current

subscribers. This can become an important consideration if you are doing

something expensive to produce the values. For example, let’s say you are making

a request to some API and notifying observers of the value returned from that

API. If you have lots of subscribers, that request is going to be executed for

every subscriber if you use a standard Observable. If you use a Subject the

request would only be executed once. There is no correct answer, the appropriate

choice will depend on the situation, it’s just something important to keep in

mind.

Creating a Simple Subject

Now that we have a basic idea of the difference between an Observable and

a Subject, we are going to take a look at the structure of a Subject in

a little more detail.

Let’s create a really simple example of our own Subject from scratch:

export interface Observer { next: (value: any) => void; error: (err: any) => void; complete: () => void;}

export class Subject { private observers: Observer[] = [];

subscribe(observer: Observer) { this.observers.push(observer); }

next(data: any) { for (const observer of this.observers) { observer.next(data); } }

error(err: any) { for (const observer of this.observers) { observer.error(err); } }

complete() { for (const observer of this.observers) { observer.complete(); } }}This is an extremely over simplified example of creating our own Subject which

is a type of observable — don’t confuse this with a “real” Subject from the

RxJS library because the example I have created here strips out a lot of

functionality and is only the most simple of simple implementations (again, the

error and complete methods don’t even do anything special, and we don’t have

the ability to unsubscribe from this subject).

We have created a class called Subject, and any instance of this Subject

will maintain an array of observers:

const emitOneToFive$ = new Subject();To subscribe to this observable stream, we pass our Subject instance an

Observer using the subscribe method. Upon receiving a new Observer the

Subject will add it to an array with all the other observers:

private observers: Observer[] = [];

subscribe(observer: Observer) { this.observers.push(observer);}This is what happens when we do this:

emitOneToFive$.subscribe({ next: (value) => console.log(value), error: (err) => {}, complete: () => {}})This observer we have created that we are passing to subscribe will be added

to the array of observers inside the Subject. To emit new data on the

stream, and notify any observers of this data, we can call the next method. We

have already seen this as well:

emitOneToFive$.next(1)This 1 value will now be passed to the next notifier for every single

observer inside of the observers array:

private observers: Observer[] = [];Which for now is just one observer, but we could have as many subscribers/observers as we want.

Recap

That was quite the lesson. As I mentioned before, we have covered a lot of new concepts and theory that you don’t strictly need in order to use observables. However, the more you understand about this behind the scenes theory stuff, the easier observables will be to reason about and you will be able to use them more effectively.

If these concepts are new to you, I don’t expect that much of what we have talked about will stick right away. As we progress through this course we will utilise some of these concepts that we have just talked about, and hopefully having this context will spark something in your brain when you get to it. I would also advise revisiting this lesson every now and then as you gain experience until all of the concepts finally do click.

You can use the following quiz to test your knowledge, but again, don’t worry if you can’t get them all. Just continue the course and come back to this later.